The Power and Possibilities of Tech in Nepal’s Gen Z Uprising

From Sri Lanka to Bangladesh, Indonesia to Nepal, youth are rising. In streets and online, they expose corruption and demand change — showing both the power and limits of tech.

What Nepal is teaching us about the role of tech in civic engagement

Like other recent protests in South Asia, young people have taken a stand in Nepal, fed up with the corruption and excesses of the political and elite classes. Videos on TikTok are mobilising tens of thousands, and there are discussions on Discord and WhatsApp on who should lead an interim government.

Two decades into the 21st century, the writing on the wall is clear: tech and civic engagement are inextricably linked. To better understand what’s happening in Nepal and how GenZ are using tech, Balance spoke to a number of activists on the ground.

The social media block, which sparked the ‘Gen Z’ protests, has been two years in the making. In 2023, the Nepali Government issued social media management directives, including mandatory registration by tech platforms to operate in Nepal. The Government claimed that the intention was to tackle fake news, hate speech, and online fraud. But critics have been flagging ex-Prime Minister K.P. Sharma Oli’s attempts to exert government control over free speech for many years.

The Asia Internet Coalition (AIC), big tech’s front group in the region, wrote to the government saying that the "proposed registration process for internet companies in Nepal presents significant administrative hurdles for our members, involving the submission of confidential documents detailing user statistics, platform activities, security measures, and tax information."

But the Government issued a final deadline for compliance in August. The ban of 26 companies, including Meta (Whatsapp, Instagram, and Facebook) and YouTube, went into effect on the 4th September.

TikTok wasn’t blocked as it had complied, and became the primary information sharing and organising channel for the protest, with videos trending widely and lively discussions occurring through comments.

Corruption, visualised

While the social media ban may have been the trigger for the protests, anger about government and elite corruption and nepotism has been building up over the years.

In Nepal, where youth unemployment stands at around 20% and where over 25% of the population live below the poverty line, the children of political and business elites flaunt their privilege online — posting everything from designer lifestyles to Cartier Christmas trees.

This led to Nepal’s GenZ adopting the #NepoBaby hashtag from Indonesia, where youth are also protesting against the misuse of taxpayer money by those in power and their families.

Satire is political

#NepoBaby trended on Nepal’s TikTok, highlighting the obscene contrasts displayed in real time. The hashtag references serious messages as well as satirical videos, resulting in collective action on the streets in a matter of days.

In other South Asian countries too, memes form a vibrant culture of political expression. Just three years ago in Sri Lanka, the power of its humorous political expression was being reflected in mass protests that forced an authoritarian president to resign. When Sri Lankans left the presidential palace they occupied in 2022, a meme captured the moment: “We are leaving. The key is under the flower pot.”

When the Nepali government blocked social media, a significant number of the youth population believed they were being censored. The perception was that the government and the elite wanted to suppress the movement against corruption. Young people, labelling themselves as GenZ, started organising protests across major cities on 8th September. It took a violent turn in the days that followed, resulting in 23 deaths and and injuries to over 1,500 protesters at the hands of the police and military.

Tech, an organising tool

The block also led to another unintended consequence for the Nepali government: it pushed citizens to less mainstream platforms like Reddit and started using software to route around the blocks.

Aabid Husain, a final year law student in Nepal, says that citizens also downloaded VPNs to circumvent social media blocks, enabling them to continue to use platforms like Instagram. A popular Instagram page titled “Generation_Z” has over 25,000 followers, and it forms one of many pages that are driving the protests and youth activism.

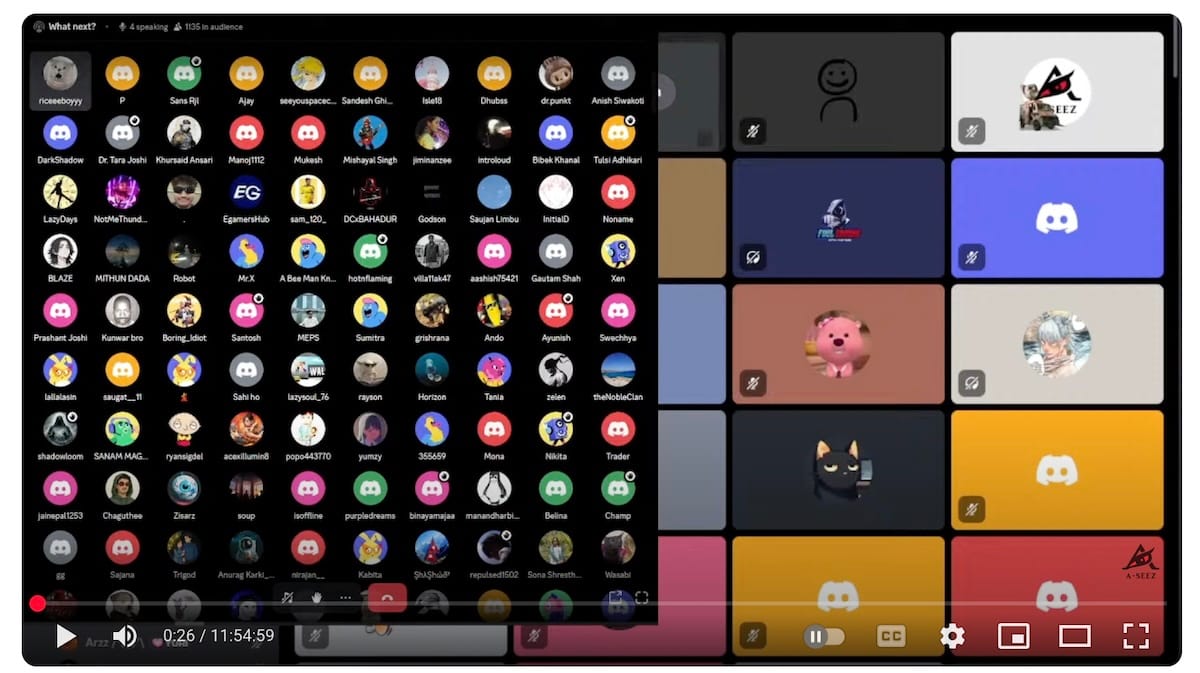

Social media platforms may be effective in promoting a cause or drawing tens of thousands to the streets, but they have limits as organising tools. At the time of writing, more than 150,000 Nepalis had joined a Discord channel, attempting to discuss who should be the Gen Z representative to negotiate with the army. Discord wasn’t designed to enable decision-making by a community this large. And there are other concerns about these attempts at tech-enabled organising.

One Nepali activist we spoke to claimed that the group is simply not inclusive. A brief analysis of the membership and the discussion suggests that young people who may not have a good grasp of English will be unable to participate in the discussions, and key figures associating themselves with the protest leadership seem to be all men.

As the protests were decentralised, there’s no “exact” leader for the youth movement, says Husain. That has led to confusion now, in the aftermath of the protests, with the State and the Army waiting to negotiate on the next course of action.

Some youth are worried that the more time passes without action, the more incentive it would be for the Army to take control of the state or to bring back the monarchy.

While the Discord channel has the most eyes on it, Husain says that it “lacks coordination”. Conversations are happening across other platforms too, like WhatsApp and Messenger.

Regardless of how Nepal maps its course in the days and weeks to come, one thing is certain: tech will play a crucial role in democratic action. From Sri Lanka in 2022 to Bangladesh in 2024 and now Nepal in 2025, South Asia has been demonstrating how citizens can collectively use online tools to mobilise. However, a deeper conversation is needed about their limitations to be inclusive and collaboration on complex decisions.