Who writes the rules? The new order of platform power

Miraj Chowdhury examines how the Trump administration’s alliance with Big Tech is reshaping not just US regulation but global digital governance — with far-reaching consequences for rights, power and accountability.

By Miraj Chowdhury

On 4 July 2025, US President Donald Trump signed into law what has come to be known as the One Big Beautiful Bill. An earlier version of this bill, passed by the House in May, included a sweeping ten-year moratorium on state-level regulation of artificial intelligence models and automated decision systems. Although that provision was stripped almost unanimously in the Senate, it was a reminder of the new administration’s alliance with big tech companies, and of what might follow in the coming days.

Trump’s intentions were clear when, within days of his inauguration, he signed Executive Order 14179, titled ‘Removing Barriers to American Leadership in Artificial Intelligence’. It overturned several Biden-era directives that had introduced ethical guidelines, procurement requirements and safeguards related to AI’s labour and social impacts. What the previous administration framed as “necessary guardrails”, the Trump administration now characterises as “unnecessarily burdensome” policies that risk stifling private sector innovation and undermining US leadership in emerging technologies.

The order came at a time when dozens of US states were introducing hundreds of bills to regulate AI — ranging from algorithmic bias protections to deepfake bans and proposals to mitigate broader AI risks. But this was not only a shift in domestic policy. It was also a signal: that the US federal government under Trump had aligned itself with Big Tech’s ambition to reset the rules of global digital governance.

In the months that followed, the rollback of oversight was accelerated. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) was gutted of Democratic leadership, hundreds of policy documents on AI and consumer protection were withdrawn from public access, and Silicon Valley was formally invited to “help make government more efficient” through a new Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE).

Some Big Tech companies had been in bitter conflict with the previous administration, particularly over content moderation, pandemic misinformation and online speech. For example, Meta had grown resentful of the Biden White House’s demands to limit harmful content. The Murthy v. Missouri case crystalised the frustration that the government was coercing social media companies to police online speech related to Covid-19, vaccines, and the 2020 election.

For many tech leaders, the proliferation of state-level bills and the Biden administration’s regulatory stance were threats to their business models, their control over digital infrastructure, and their capacity for unbridled innovation in the face of Chinese competition. The growing sense of government interference created fertile ground for an alliance with a political figure who promised to simply “leave them alone” or, better yet, clear their path. When Mark Zuckerberg publicly admitted in 2024 that Facebook had over-complied with White House pressure to suppress Covid-related satire and stories about Hunter Biden, he wasn’t just deflecting blame — it seemed like he was signalling a new alliance.

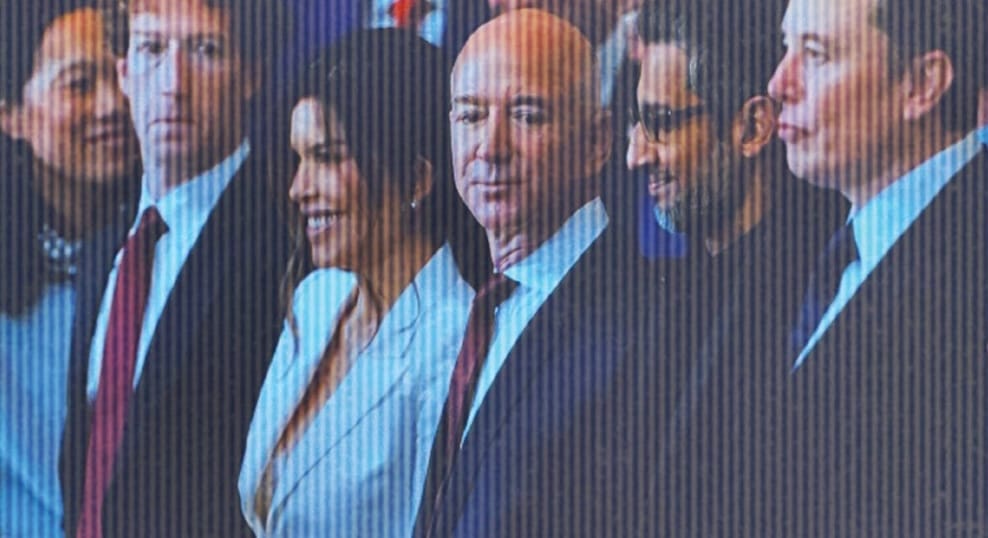

By mid-2024, the realignment was underway. Elon Musk founded the America Super PAC. Andreessen Horowitz released its 'Little Tech Agenda', positioning tech deregulation as a patriotic cause. The Trump campaign was flooded with contributions from platform billionaires and crypto magnates. Meta and Amazon each donated $1 million to Trump’s inauguration fund; OpenAI, Coinbase and PayPal followed suit. Tech leaders, once hesitant to openly back Trump, now viewed him as the president willing to help them expand.

While domestic deregulation was anticipated and has visibly taken shape over the past few months, something even more ambitious is unfolding: an effort by US tech firms, backed by the federal government, to influence legal regimes well beyond their national borders.

It looks as if the European Union will be the primary battleground, if it isn’t already. In Brussels, tech platforms are actively challenging core provisions of the EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA) and AI Act. Lobby groups including the Computer & Communications Industry Association (CCIA) have called on the EU to pause enforcement, citing “damage to innovation”. Meta and TikTok have filed legal complaints against the supervisory fee system. European NGOs warn that Washington and Silicon Valley are working together to water down Europe’s digital agenda.

The rush to influence global policies is also visible in major tech platforms’ lobbying efforts. In the first quarter of 2025 alone, Google spent $3.01 million on lobbying while Meta spent about $8 million — the highest Q1 spend to date. Their filings frequently mention cross-border data flows, EU–US trade negotiations and digital regulation, highlighting concern with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and other digital laws.

The influence is not centred around one market alone. In a recent disclosure, Meta reported lobbying Congress and the US Trade Representative, among others, on what it called “international digital policy” — including privacy, data localisation, content moderation and regulatory proposals — in Bangladesh, Pakistan, India and Nigeria. Google has engaged in lobbying around export controls for emerging technologies, cross-border data flows and digital trade provisions in free trade agreements, signalling a broader concern with regulatory fragmentation and data localisation trends worldwide.

In a 2025 commentary for Tech Policy Press, Gordon LaForge, a policy analyst, argued that US tech firms have increasingly acted as foreign policy players — negotiating with governments, shaping trade norms and influencing regulation abroad. A Tech Policy Press series titled ‘The Coming Age of Tech Trillionaires and the Challenge to Democracy’ has also warned that the global influence of US tech is no longer just economic or cultural, but also legal and institutional. The global political impact should not be overlooked. According to a commentary published on Foreign Policy: “Silicon Valley is becoming an instrument of U.S. coercion, and that’s a danger to each and every country”.

The global consequences of this influence aren’t just shaped by policies, but also by where they land. In the EU, strong institutions and independent courts can enforce user protections in a better way. But in an increasingly authoritarian world, the same regulatory tools — like data localisation mandates or content takedown laws — can be repurposed for surveillance, repression and political control, depending on governance and political environment. A policy that protects users in Brussels can chill dissent in Dhaka or Lagos.

This is why, for people in many of these countries, legislation can be a double-edged sword. On the one hand, less regulation might mean more freedom, but it also means ceding more power to unaccountable corporations. On the other, demanding more regulation may lead to censorship and repression. Where institutions are weaker, civil society is under pressure, and enforcement is often politically captured, the same influence from platforms — reinforced by US backing — may tilt digital policy even further toward corporate or state interests. The result may be weakened user protections.

This raises several critical questions for countries in Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Middle East. As we increasingly live within the infrastructure, rules, and norms set by big tech companies — without the bargaining power to influence their decisions — who defends the rights of users? Does the state–tech alliance mean a drastic shift from rights to power? Will states demand more control over content in return for letting tech giants shape the future of AI and commerce? And, most importantly, what happens when these dynamics intersect with geopolitics?

During the recent India–Pakistan conflict, in a sign of sweeping censorship, over 8,000 accounts — including those of journalists, creators and news outlets from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, China and Turkey — were blocked on X within Indian territory. YouTube geoblocked Pakistani and Bangladeshi news channels in India; Pakistan retaliated by banning Indian digital content. This spiral of platform-enforced censorship raises urgent questions about whether companies, lobbying to shape laws, are also becoming too willing to carry out political takedowns in return for regulatory favor.

No matter how the coming years unfold, there will likely be more pressure for tech deregulation across the world, coming from the US state–tech alliance. The impact of this on countries and their people will almost certainly be uneven. In much of the world, the protections you enjoy online — over your speech, data, safety — will increasingly depend on where you live, who governs you, and how much revenue platforms see in your market.

Writer bio: Miraj Chowdhury examines how the Trump administration’s alliance with Big Tech is reshaping not just US regulation but global digital governance — with far-reaching consequences for rights, power and accountability.