Documenting resistance, building alternatives: The App Censorship Project and the struggle for digital freedom in Asia

From app removals in China to quiet compliance in Hong Kong, Benjamin Ismail traces the rise of platform-enabled censorship and the complicity of global tech giants in enabling digital authoritarianism.

By Benjamin Ismail

Across Asia, digital authoritarianism has increasingly tightened its grip on online freedoms, restricting access to information and communication through a combination of heightened surveillance, mandates on internet infrastructure providers and strategic cooperation with global technology platforms. Governments across the region are leveraging the centralised control of mobile ecosystems to enforce censorship with unprecedented precision and scale.

Mobile devices are now the primary gateway to the internet for billions of people, which means that platforms like Apple’s App Store and Google’s Play Store have become critical arbiters of online speech and access. Once seen as gateways to innovation, these app distribution monopolies are now also tools of suppression used by authoritarian regimes to remove apps that offer privacy, secure communication or access to independent media. By complying with takedown requests, tech giants become complicit in enabling censorship, eroding fundamental rights and silencing dissent.

A platform for transparency and accountability

The App Censorship Project officially launched in 2023, but its origins trace back to the creation of AppleCensorship.com in February 2019. Since its inception in 2008, Apple’s App Store had operated as a black box with little public understanding of how or why apps were removed. AppleCensorship.com was thus born out of the need to expose the opaque nature of the company’s app curation process and force transparency into an ecosystem that had long evaded scrutiny.

The catalyst for the initiative was Apple’s intensifying cooperation with the Chinese government. Censorship escalated following Apple’s entry into China in 2010. One of the first major app removals involved politically sensitive figures like the Dalai Lama and Uyghur leader Rebiya Kadeer. In 2013, Apple removed FreeWeibo, an app we created to archive censored Weibo posts, further illustrating the company’s growing complicity.

By 2017, Apple’s compliance reached a new height: over 600 Virtual Private Network (VPN) apps were removed from its China App Store after demands from Chinese authorities. This mass takedown was the first categorical ban of its kind in a major app store, executed with little public disclosure. Following minimal pushback from legislators and the media, Apple resumed business as usual.

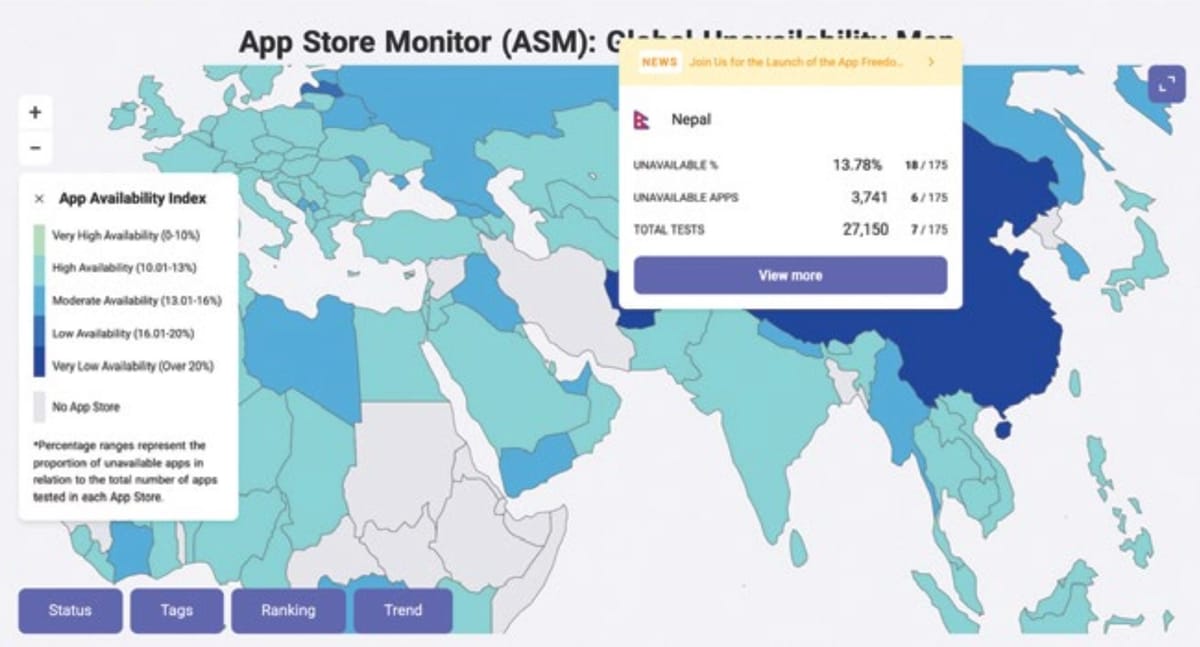

This set the stage for AppleCensorship.com, a real-time monitoring platform powered by the App Store Monitor (ASM). The ASM tracks app availability across all 175 of Apple’s App Stores, providing a searchable and systematic record of removals.

While Apple was the initial focus, Google’s Play Store also plays a critical role in the app distribution ecosystem. Recognising the need for comprehensive monitoring, the App Censorship Project expanded in 2024 with the launch of GoogleCensorship.org, powered by the Play Store Monitor (PSM). This expansion allows comparative analysis across both dominant mobile platforms, exposing censorship trends and regional disparities.

The forthcoming AppCensorship.org will serve as an aggregated hub, bringing together datasets from both AppleCensorship.com and GoogleCensorship.org to deliver a holistic view of app suppression worldwide. The idea is to enable cross-platform transparency, support advocacy efforts and inform digital rights strategies.

Turning data into action

Despite the immense size of Apple and Google’s app stores — each hosting around two million apps — what initially seemed like a needle-in-a-haystack search for censorship quickly revealed deeper patterns. Repeated digging uncovered systematic and politically driven restrictions. We observed a clear and consistent unavailability of LGBTQ+ apps across much of the Middle East and Gulf region, and came to understand just how profoundly isolated China’s App Store is from the rest of the global ecosystem. Our research also brought to light a range of situations, including in Russia and Hong Kong, where Apple compromised its publicly stated commitment to human rights in response to state demands or regional pressures.

One particularly striking example occurred last summer, when Apple quietly removed more than 60 VPN apps from the Russian App Store under orders from Roskomnadzor, the Russian federal agency overseeing mass media in the country. These ‘silent’ takedowns severely limited Russian users’ ability to access secure web services and communicate freely.

The epicentre of platform-enforced censorship

China stands at the centre of this new model of censorship. As mentioned, it wasn’t long after Apple entered the Chinese market that they began engaging in political filtering. When U.S. senators criticised their sweeping 2017 ban of VPNs from the Chinese App Store, the company insisted that it was merely complying with local laws. It was the first known instance of a platform executing a full “categorical ban”. VPNs, essential for circumvention and privacy, were entirely blocked in China.

In the years since, Apple has continued to quietly remove apps deemed objectionable by Chinese authorities. As of June 2025, the ASM has logged 18,801 unavailable apps in the China App Store — an astonishing 28.12% unavailability rate, more than double the global average. The apps more affected include those relating to news, books and social networking. Apps touching on religion, LGBTQ+ issues, Tibet or Uyghur identity are consistently targeted. The result is a tightly controlled digital environment where even basic information tools are inaccessible.

A 2023 analysis comparing the 100 most downloaded apps worldwide found that sixty-six were unavailable to iOS users in China. Just four of the top 100 global apps appeared on China’s “most downloaded” list — all four were domestic Chinese services. By contrast, only eight of the top 100 apps were unavailable in the U.S. App Store. This illustrates the unprecedented level of digital isolation faced by Chinese users.

Despite facing increasing repression since the 2014 Umbrella Movement and an intensified crackdown beginning in 2019, Hong Kong has not yet mirrored the extreme app censorship of mainland China. Still, the situation is far from reassuring — it’s still significantly more restrictive than stores in countries we classify as “free”.

In late 2022, we began assessing the Hong Kong App Store, using data from both AppleCensorship.com and external sources. Our report, Apps at Risk: Apple’s censorship and compromises in Hong Kong, examined Apple’s compliance with censorship demands in the Special Administrative Region. Many residents rely on apps that are banned in mainland China to access information and communicate — as the master of the App Store, Apple could potentially become a ‘kill switch’ for censors.

We found that Apple, likely under pressure from Hong Kong authorities or the Chinese central government, had already repeatedly removed apps deemed illegal or politically sensitive. As of November 2022, more than fifty VPN and private browsing apps have already disappeared from the Hong Kong App Store. The report also noted the global removal of several news and media apps, suggesting that Apple may be engaging in pre-emptive self-censorship or acting on behalf of authorities. Crucially, Apple has never made a public commitment to safeguarding Hong Kong residents’ digital rights, leaving its future stance on censorship under pressure highly uncertain.

No simple correlation

A key observation from our research is that there’s no direct correlation between a country's broader digital authoritarianism and the state of its app distribution platforms, whether it’s Apple’s App Store or Google’s Play Store. For example, Vietnam has heavily cracked down on independent journalism, civil society forums and political bloggers, yet we have found no significant app takedowns. The same applies to Laos, Cambodia and, to a lesser extent, Pakistan.

There are several plausible — but difficult to verify — explanations for this.

First, a low perceived threat: authorities in these countries may view app-based platforms as less significant due to low user engagement or mobile penetration and therefore see no need to interfere.

Second, failed or filtered takedown attempts: as suggested by Apple’s 2018 transparency reports, governments may have submitted removal requests that lacked proper legal justification or focused solely on non-political content (for example, illegal gambling, child exploitation or drug-related apps).

Finally, corporate resistance: in some cases, tech companies may exert enough economic and political leverage to dissuade local authorities from issuing such requests.

Given the opacity surrounding both state action and corporate compliance, these patterns are difficult to confirm definitively, but the data nonetheless highlights important trends.

Some countries do show growing signs of platform-based censorship, particularly on the Google Play Store. In Myanmar, the military junta has increasingly tried to control the flow of information online. In India, under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s administration, there have been documented attempts to suppress dissent and restrict content online.

Both countries exhibit a higher rate of app unavailability on Android platforms, which is significant given that the majority of users in these countries use Android over iOS. This suggests that censorship strategies are increasingly adapting to local user demographics and platform dominance.

Building a just and resilient digital future

The App Censorship Project isn’t confined to observation and documentation; it’s fundamentally an initiative for systemic transformation. Drawing from its research and on-the-ground findings, the Project advances a series of bold and actionable reforms aimed at reshaping the digital ecosystem into one that’s more transparent, accountable and just.

One of the Project’s central demands is for mandatory transparency reporting: technology giants such as Apple and Google should be required to publish detailed disclosures of all app removals, including the specific reasons for each takedown and the jurisdictional contexts in which they occur. Such transparency is essential for meaningful public oversight and accountability.

Beyond disclosure, the Project advocates for the establishment of independent oversight mechanisms. These would take the form of third-party bodies with the authority to review, challenge and potentially overturn app removal decisions, thus ensuring that such actions align with international human rights standards rather than opaque corporate or governmental interests.

The Project also calls for legal protections for sideloading and the development of alternative app stores everywhere. We need to dismantle the monopolistic control of dominant platforms. By enabling users and developers to access and distribute apps through open, competitive channels, these reforms would reinforce digital autonomy and innovation.

Finally, the Project urges investment in decentralised and community-governed platforms. Federated, open-source technologies, built and maintained by communities rather than corporations, offer resilient alternatives to centralised gatekeepers. These tools not only resist censorship and surveillance but also foster inclusivity and democratic governance in the digital sphere.

Together, these proposals form a blueprint for a more equitable digital future, one in which corporate complicity is challenged, user agency is restored and civil society is empowered to shape the digital spaces it inhabits.

Towards digital freedom in Asia… and beyond

The App Censorship Project represents more than resistance — it embodies a proactive vision of digital autonomy and resilience. By combining rigorous documentation, targeted advocacy and visionary proposals, the Project provides a comprehensive framework to not only challenge but dismantle centralised digital gatekeeping.

As governments escalate digital control, transparency and accountability will be essential to safeguarding online freedom.

Ultimately, the success of this effort hinges on global cooperation, meaningful policy reform and sustained grassroots resistance. While regulatory change may be difficult to achieve in many local contexts, there remains significant potential for impact in jurisdictions such as the United States — where major tech companies are headquartered — and in the European Union, where there’s been a growing willingness to confront platform power through legislation.

To that end, it’s essential that civil society actors and digital rights defenders in countries facing rising digital authoritarianism recognise the urgent threat posed by Big Tech’s unchecked gatekeeping power. These corporations operate with virtually no transparency obligations and little to no accountability mechanisms, yet their decisions shape access to information on a global scale. The risks they pose are not confined to any single region; they imperil the future of the open internet everywhere and contribute to the accelerating fragmentation of the internet into national or corporate-controlled silos, undermining its universality and openness.

Through its relentless monitoring and bold reform agenda, the App Censorship Project is working to ensure that digital freedom remains not just an ideal but a concrete possibility, both for Asia and for the world at large.

Writer bio: Benjamin Ismail is Campaign and Advocacy Director at GreatFire and leads the App Censorship Project. A long-time advocate for freedom of information, he previously worked with Safeguard Defenders and led Reporters Without Borders’s (RSF) Asia-Pacific desk, where he spent seven years campaigning against censorship in China and other authoritarian regimes.